By Charles Igwe

The Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), also known as the Biafran War, remains one of the darkest periods in Nigerian history. The conflict, which arose from the secession of the southeastern region of Nigeria to form the Republic of Biafra, led to immense suffering, starvation, and the loss of millions of lives, particularly among the Igbo people. Amidst this devastation, the Catholic Church stood as a haven of hope, offering humanitarian aid, spiritual support, and shelter to those suffering the consequences of war. At the forefront of these efforts were both the foreign missionaries and the indigenous clergy and religious who risked their lives to provide relief in the face of unimaginable challenges. Together, they formed an extraordinary network of compassion and service that became a lifeline for many during the darkest days of the war.

As the war escalated, the Igbo people found themselves cut off from essential supplies due to the Nigerian government’s blockade of Biafra. The resulting famine, particularly in 1968, claimed countless lives, with children being the most affected. In response to this crisis, the Catholic Church mobilized a massive relief operation. This effort was led by foreign missionaries, especially Irish and French priests and nuns, many of whom had been stationed in Igboland for decades, as well as indigenous clergy who had grown up in the communities now ravaged by the war.

Archbishop Charles Heerey, the then-Archbishop of Onitsha, played a key role in organizing these efforts. He coordinated with the global Catholic Church, appealing to organizations like Caritas Internationalis and Catholic Relief Services for aid. Despite the dangers of operating in a war zone, the Church ensured that food, medicine, and other essential supplies were airlifted into Biafra through a clandestine relief network. Catholic missions became makeshift hospitals, feeding centers, and shelters for refugees fleeing the frontlines. The Church’s humanitarian efforts also extended to organizing international advocacy. Catholic leaders in Biafra appealed to the Vatican and Western governments, seeking diplomatic solutions to end the war and alleviate the suffering of the people. Their advocacy, though often hindered by political interferences, was instrumental in raising awareness of the Biafran plight on the global stage.

While the contributions of foreign missionaries have been widely documented, the role of indigenous clergy and religious during the war was equally significant and deserves recognition. Many of the Igbo priests, nuns, and lay religious workers, who had deep personal ties to their communities, were at the forefront of relief efforts, providing physical and spiritual comfort to the displaced and wounded.

One of the most notable figures was the late Bishop Godfrey Mary Paul Okoye, of Enugu, who was instrumental in maintaining the morale of the people during the war. Despite the dangers, he continued his pastoral duties, administering sacraments and providing spiritual counsel to both soldiers and civilians. His leadership was crucial in keeping the faith alive in a time when many felt abandoned by the world. Bishop Okoye also played a role in peace efforts, advocating for an end to hostilities and for dialogue between Biafra and Nigeria. Nuns from various religious orders, including the Daughters of Divine Love (founded by Bishop Godfrey Okoye in 1969), worked tirelessly in hospitals and refugee camps, providing care for the sick and dying. These local religious figures were active participants in the Church’s relief efforts. Their deep understanding of the local culture and their ability to communicate in the Igbo language enabled them to connect with the suffering population in ways that foreign missionaries could not. This partnership between indigenous and foreign clergy created a powerful synergy that amplified the Church’s impact.

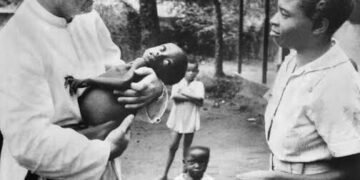

More so, Catholic missions across Igboland became sanctuaries for the displaced during the war. Schools, seminaries, and convents were transformed into shelters where people could find food, medical care, and protection. The missions became oases of safety in a landscape devastated by war, and the priests, nuns, and lay religious within these missions worked tirelessly to provide for the needs of the people. At the height of the war, when starvation and disease were rampant, it was the Catholic missions that set up feeding centers for malnourished children. Many Igbo children owe their lives to the porridge and relief packages distributed by these centers. The nuns, often working with minimal resources, displayed extraordinary resilience in caring for these children, treating them with the compassion of mothers even as the bombs fell around them.

Beyond the physical relief provided, the Catholic Church also played a crucial spiritual role. As war shattered families and communities, many people turned to the Church for solace. The clergy conducted Masses in bomb shelters and open fields, providing moments of respite where people could find hope amidst the chaos. Confessions, baptisms, and anointings of the sick became regular sacraments during this time, and the Church’s presence gave people the strength to endure. Many accounts from survivors of the war recall how priests and nuns would walk through the camps, comforting the dying and praying with families who had lost everything. The presence of the Church became a reminder that God had not abandoned His people, even in the midst of unimaginable suffering.

The end of the Nigerian Civil War in 1970 brought relief, but the scars of the conflict would remain for generations. The Catholic Church’s role during the war, however, left a lasting legacy. The Church had demonstrated the power of faith in action, providing both spiritual and physical sustenance in a time of extreme hardship. Its dedication t to the welfare of the people earned it immense respect and further solidified its position as a central institution in Igbo society.

In the post-war period, the Church became a key player in the rebuilding of Igboland. Catholic schools, hospitals, and churches, many of which had been damaged or destroyed during the conflict, were rebuilt, and the Church’s influence continued to grow. Indigenous clergy, many of whom had been young priests or seminarians during the war, took on greater leadership roles, guiding the Church into a new era of growth and development.

As the Church in Igboland continues to flourish today, its legacy from the civil war remains a source of pride and inspiration.